My improvement approach started with attempts at ‘good science’ using logic and reason. This was the right approach, with good outcomes for patients.

However, after a secondment where some of the situations required dealing with uncertainty, tipping points of change and elements of disorder, I had to adapt.

The compulsion to bring order to a complex adaptive system is like a dog chasing its tail. So, I chose a different approach.

This involved changing the logic with which I approached a problem or situation.

This is the second blog in a two-part series on worldviews in improvement. For an outline of different worldviews and how they relate to improvement, see my first blog.

Logic and improvement in complex systems

In Social Research: Paradigms in Action, Blaikie and Priest say it is not possible to avoid adopting a worldview, but they do think you can make some fundamental choices. There are three main logics to consider when approaching improvement projects.

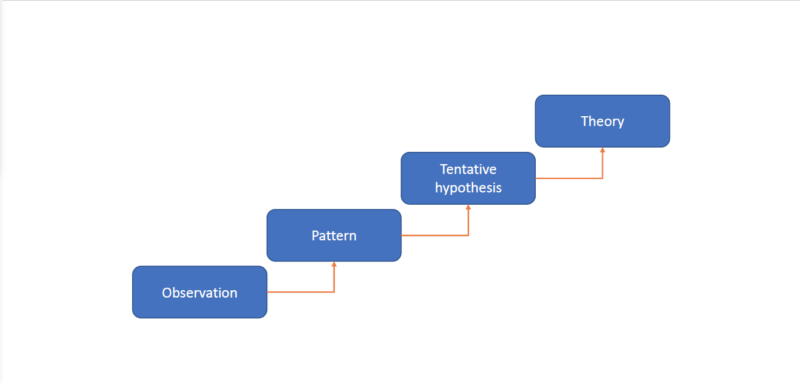

Inductive logic of inquiry: the practitioner starts in a bottom-up way with observations of the phenomenon or people’s own subjective interpretations. This is intuitive to clinical staff. The practitioner then develops questions or hypotheses to investigate the phenomenon. As these questions or hypotheses are confirmed or refuted the practitioner can build up a picture of what is going on. This is usually then called a ‘theory of change.’ Most of the time, a theory of change comes about by the next logic.

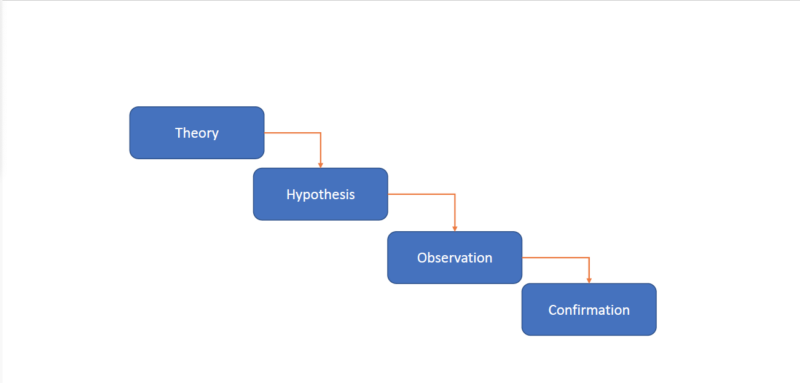

Deductive logic of inquiry: the practitioner starts in a top-down way. This is something many of us are already familiar with. This logic is usually developed from a set of existing principles, e.g., model for improvement or Toyota production system principles. It takes pre-existing laws or principles that are already formulated into a theory or model and applies them to a new scenario. In turn, this produces a new question, i.e., what did you learn from the last Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycle that created some curiosity as to what was going on? Because this type of logic starts with a theory of change, there is a risk that a systemic element has been missed.

Abductive logic of inquiry: the practitioner is usually driven by a phenomenon or social problem itself. This is the approach I realised I was taking. The practitioner tries to explain why it is occurring, why now and in what ways. They may compare themes and dynamics that explain the issues from other situations, professions or past projects to help shed light on the issue. This can come off as challenging the status quo, when applying the concept of falsification to commonly held absolutes. For example, if the common discourse is that all crowds will riot, but there is evidence of peaceful crowds, then that ‘law’ does not always hold true. Mixed methods to triangulate findings seems to reside here.

Changing the logic for better outcomes

I believe systems methodologies and other approaches from across disciplines can offer insights into other traditions of understanding. I now consider what I understand about the situation and adapt my logic and reflect on my worldview. I do not believe it to be wholly inescapable, but by appreciating and reflecting on them, we can perhaps sidestep some pitfalls in thinking.

Changing the logic is not to be confused with changing the methodology. For example, with a classic improvement approach of define, measure, analyse, interpret and control (DMAIC) which has a deductive systematic logic element to it, switching out the tools for something qualitative instead of quantitative does not make it inductive nor systemic. The logic of method here, i.e. the methodology, is essentially the same. Only the tools have been changed.

Starting with a systemic approach such as an appreciative inquiry to understand the situation more holistically and then applying DMAIC would be considered a mixed methods approach.

Systems thinking and complexity science can offer insights into diverse ways of understanding. (See the poster from Ecolabs linked at the end of this blog if you want to learn more about those concepts.)

While worldviews may not be wholly inescapable, I believe that appreciating and reflecting on them can help us sidestep some pitfalls in our thinking.

Where do we go from here?

If we, as improvement practitioners, are to cultivate sustainable change, we need approaches to match the wicked problems we encounter. Dan Harley discusses some of these in his recent blog (see related links).

I invite you to consider incorporating some research principles, systems thinking and complexity science into your improvement practice.

Reflect on whether your chosen methodology aligns to the system it is to be applied to or whether it has been chosen because of the dominant worldviews on the project.

The best advice I ever had when something was not working was, ‘change your approach.’ I hope this blog might help you do that.

Join the conversation

What alternative approaches do you find useful? Let me know in the comments below. You can also continue the conversation on the Special Interest Group (SIG): Complexity approaches to support quality improvement.

Further resources

The Visual Communication of Complexity – May2018 – EcoLabs (cecan.ac.uk)

Comments

Thomas John Rose 10 Dec 2023

Not sure that six sigma is right for the nhs (DMAIC). It's expensive and there is a better solution. It;s called 'Process Management' starting with 'Standard Work'. You just need to learn how to do it. Cost nothing but some time and maybe a book. Or I could help.

Andrew Ware 10 Dec 2023

I agree regarding DMAIC as a single ontological approach. Unless it’s a process that is normally distributed, it’s the correct fit.

A multi-ontological approach as described by Snowden is required, albeit requiring the systemic approach first.

Even if worldviews are inescapable, aligning methods can be a conscious choice.

There is the element of first and second order cybernetics to change which I am thinking about writing a blog about as first order relies on a method and 2nd order requires the practitioner to be situated with the situation and take a reflexive approach.

Thomas John Rose 14 Dec 2023

Thank you for your comment Andrew. You say that Toyota have a top down approach. Toyota start at the 'process'; you can only do that if you have defined the 'process'. This is not done in the NHS as they don't understand 'process' - it's what you do! It's what you are trying to improve. It's what Juran and Deming teach and it's a bottom up approach. KISS

Andrew Ware 15 Dec 2023

I think that is a misinterpretation of what I said. Deductive logic from the perspective of the NHS improvement practitioner is 2nd order problem orientated (as its hard not to interact with others - but it happens and fails) and therefore top-down from their worldview.

An inductive approach can be foremost first order, pulling on their intuition, built from their experience, feedback and practice i.e. expertise - the gut feeling of what is wrong and what to do.

This was not in the context of a hierarchal mandatory approach which is sounds like you have read, but I would contest if you didn't adopt the TPS approach at one of their factories, you wouldn't last long, and the only bottom approach is that you would be out on it.

I am TPS & SOPK trained and I agree it starts with the process, rather than the wider situation, the multiple perspectives of what the 'problem' is or the boundary judgements made by those perspectives. These are second order conversation with another or a third order conversation with more people when the problem is wicked and the issue cannot be highly defined as is not carried out by one person. i.e. it is not a process. Often the term problem is interchanged with 'process', which makes the latter an assumption to be true. Making those trying to K.I.S.S. look foolish when they don't realise the problem is complicated or complex, or an even worse, it is an activity (multiple people undertaking handover tasks sequentially) rather than a process. Usually this is why the data is not normally distributed. A mismatch in the ontology and epistemology often common with single ontological sensemaking approaches providing short term solutions.

Usually because in the context of using TPS, its design for discrete 'tameable' problems. I say tameable rather than 'tame problems' used by other approaches as it can appear insulting. Sometimes it is like trying to tame a lion. Sometimes its watching them in their natural habit to learn (abductive logic). It's choosing the right approach for the right situation.

It would be interesting to know your perspective of NHS Wales , as I'd say here in NHS Wales we are pretty darn good at understanding the process , when it is a process problem. We have plenty of organisaitons in NHS Wales teaching methods and tools from Deming, Juran and Shewhart and beyond including other lineages and disciplines outside of process improvement.

Thomas John Rose 13 Jan 2024

Andrew, If you could send me an example of your process documentation I will be in a position to reply to your post. I now use the term NHS Standard Process rather than the LEAN Standard Work. It makes it easier to differentiate between clinical activities/tasks and operational activities/tasks. I find that there is little understanding of this. Looking forward to your response. t.rose.1@bham.ac.uk