I would like to share something I have been thinking about for a while but not really had the language to communicate before now.

It starts with a question: what is your worldview?

This is not to be confused with your perspective; where you are situated and what you think on a given subject.

Worldview or ‘weltanschauung’ in systems thinking is taken from the German to mean ‘an attitude towards or an appreciation of the world from a standpoint.’

Peter Checkland, a renowned systems thinker in the systems community, preferred this term to ‘worldview.’

It is used interchangeably to mean concept or understanding.

Understanding different weltanschauungs in a research or improvement project is important because it allows each observer to attribute meaning to what is being observed.

This blog is the first of a two-part series looking at worldviews and how they relate to improvement.

Understanding worldviews

One of the principles of social and psychological inquiry is that worldviews are inescapable. This is within the realm of research, but I believe it to be applicable to improvement.

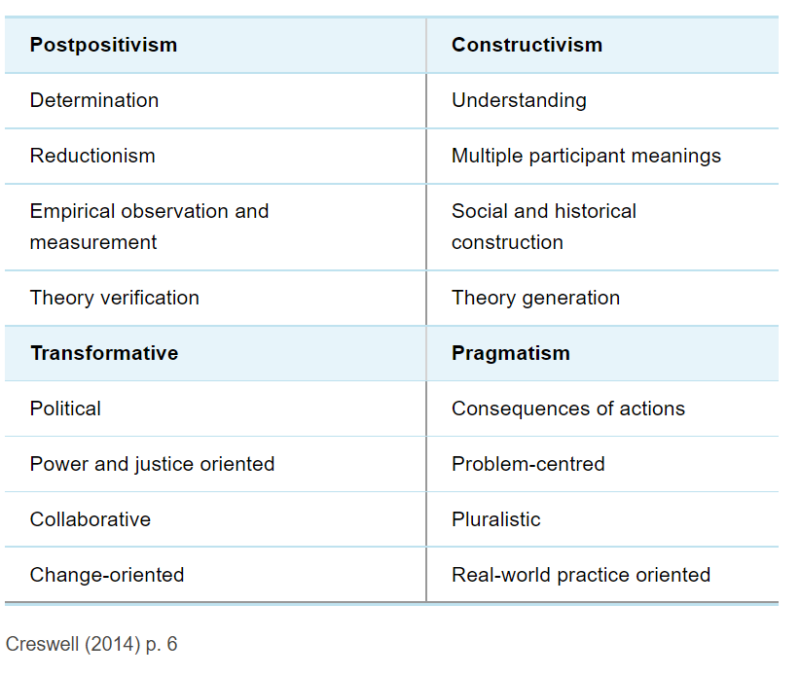

Creswell outlines four worldviews that can influence research design. These are post-positivism, constructivism, transformative and pragmatism. See the table below.

A post-positivist worldview holds that all ‘genuine’ knowledge is either true by definition or derived by reason and logic from sensory experience. Other ways of knowing, such as intuition or reflection, are considered meaningless.

Those of us who are taught reflective practice might be surprised at that. It was popularised in the 19th century but has seen a decline more recently. In research, as well as improvement, there are implications for this position. It relies on empirical observation and measurement and can be reductionist, although it can be used to verify a theory or determine a cause.

A social-constructivist worldview describes the belief that truth and knowledge is constructed with others. This can help with theory creation, highlight multiple perspectives and their meanings and bring forth understanding of phenomena.

A transformative worldview takes the standpoint that there is a power imbalance, an inequity or a lack of equality. It can be political, and highlight needs for justice. This is done collaboratively and is opportunity orientated as opposed to problem orientated. Rather than focusing in on the problem, people with transformative worldviews seek to make it irrelevant by doing something to make the problem invalid.

A pragmatic worldview can highlight the consequences of actions (or inaction for that matter), engages multiple perspectives like social constructivism but is problem-centred and focused on real world practice.

Researchers widely accept that they are not explicitly directed into their worldviews but adopt them.

Worldviews and methodologies

Each worldview has a propensity to either qualitative or quantitative methods.

Post-positivists usually use quantitative methods. Social constructivists may mainly use qualitative means. Pragmatists and those with transformational worldviews may use mixed methods.

These are not fixed rules. You may have worldviews that mix methods, but your approach will still be steeped in your worldview.

It baffles me that some research will only get published in certain journals depending on its methods, rather than what it found or its utility. We need to reflect on that. How tied are we to methods in improvement that fit a familiar discourse?

Applying worldviews to improvement

Improvement practitioners advocate measurement heavily. This is usually quantitative and displayed on run charts, etc. In closed systems (no transference of materials only energy/information), such as highly controlled environments like radiology or labs, there are rules and order. This leaves fewer unknowns to worry about.

What about other situations of concern where causality is not as well-known, and the rules are not obvious?

Reflecting on what our worldview is and how we go about improvement could help us to improve our practice.

Perpetuating a worldview when there is a mismatch to the situation can ruin relationships and cause improvement work to become stagnant or even unsustainable.

Join the conversation

Please use the comments below to let me know what approaches you have found useful. You can also join the Special Interest Group (SIG): Complexity approaches to support quality improvement.

Learn more

Visit the Open Learn resource page: Systems Thinking Hub – Open Learn – Open University