Nurses in the 21st century must possess the necessary knowledge and skills in order to provide safe and competent care to a diverse range of patients with multiple health conditions.

The process of acquiring knowledge and abilities commences during the pre-registration phase of a student nurse’s training. It is crucial to establish the groundwork for future practice during this period. I have been delighted to receive some extremely positive student nurse testimonies regarding their placements within care homes within Scotland.

As a prerequisite for their pre-registration university degree, it is necessary for every student nurse to be provided with opportunities and an adequate amount of time to gain knowledge, enhance their skills, and establish links between their theoretical comprehension and practical implementation. This is achieved by utilising practice learning contexts, particularly in care home settings.

Care Home Education Facilitator (CHEF) nurses are a national network of registered nurses in Scotland who support learning and development for practitioners in care environments, primarily for older adults.

The CHEF nurses enable nurses and other care home professionals to supervise and assess students. They act as practice supervisors or practice assessors, as defined by the Nursing and Midwifery Council, in practice learning environments.

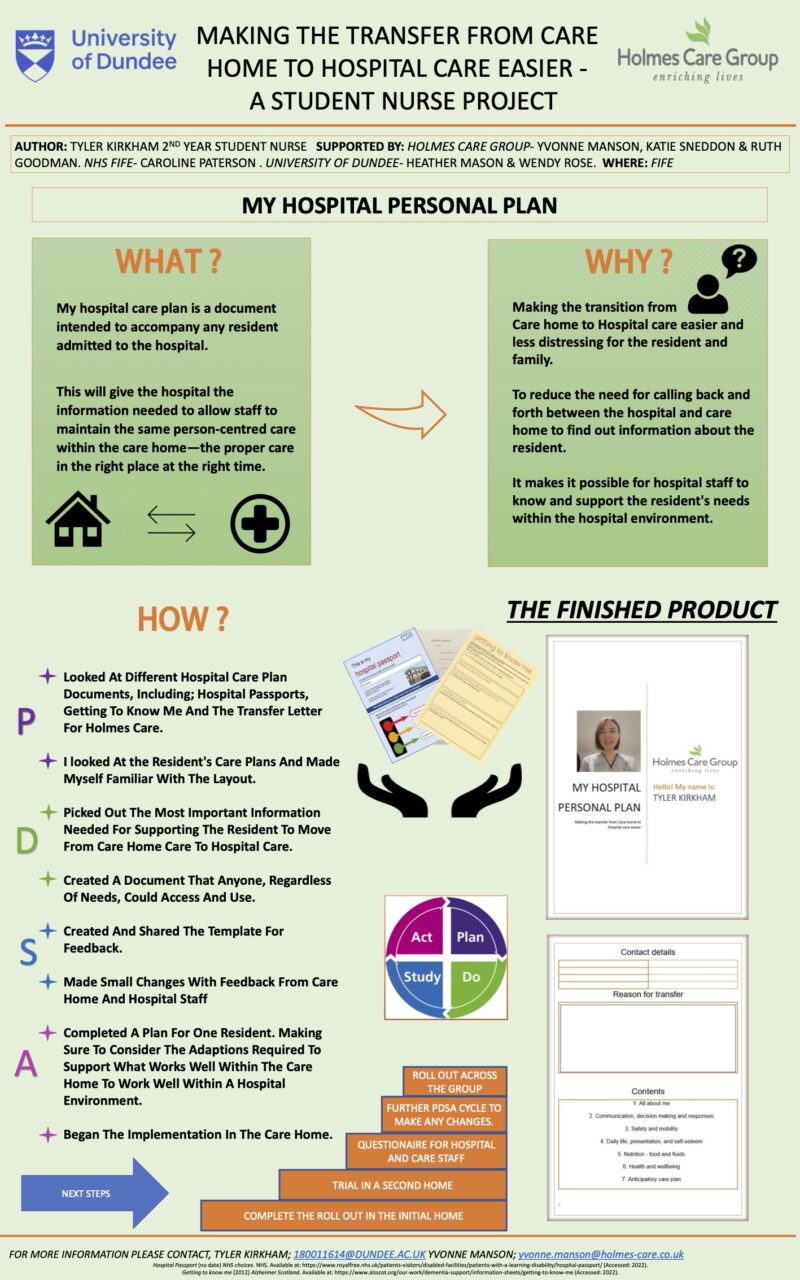

A CHEF nurse recently introduced me to a student nurse on a placement in one of the Holmes Care Group care homes. The student nurse had an improvement idea to support patients with dementia during hospital stays. The student nurse was supported to develop her concept.

For nurses in care homes, there is an ever-changing need to balance giving patients living with life-limiting conditions care that provides support and encouragement while respecting their preferences for self-management as their condition progresses.

The student nurse’s role included ways of improving not just the health of patients in the care home but also their happiness and overall wellbeing. Her role gave her the opportunity to work across both clinical and non-clinical areas of the service. This offered her a complete system overview of the way patients were cared for and how care was delivered. The student also benefited from working as a nursing support worker within the NHS and had also spent some time as a support worker in a care home. Each of these experiences provided her with a unique opportunity to see the patient journey through different lenses.

The student nurse was inspired to consider how a familiar tool – the hospital passport, normally used for patients with learning disabilities – might be adapted for those living with dementia.

Hospital passports for those living with life-limiting conditions

Hospital passports are designed to hold a rich source of personalised information to improve communication and enable self-management for patients in a range of care settings. As well as information about their health needs, a hospital passport has information about who the patient is as a person and how they prefer to be cared for. It may include details such as:

- personal interests

- likes and dislikes

- how they prefer to communicate

- decisions around treatment (consent)

- details of lasting power of attorney

Having this information to hand allows all those involved in the patient’s care to have a greater appreciation for the individual as a whole person, and simple adjustments they can make to provide care that is person-centred, high quality and compassionate. It allows care to move from a procedural, mechanical approach to a personalised, flexible approach tailored to the patient’s personal tastes.

For example, some patients who need help washing themselves may want to be washed by someone of the same sex, while others may have no preference. Some may find it difficult to eat if they are in a noisy environment, or that their mental capacity is better in the morning but not great in the evening; or the other way around. Some may prefer to dress themselves, while others may find this difficult and like to have help.

These are just a few examples of the things that can have a profound impact on an individual’s experience of the quality of their care.

How a passport is created

To build a meaningful hospital passport, you need to use a combination of expert listening and observational skills, empathy, and clinical training. In the case of this student nurse, she worked closely with the patient and their family to build a holistic understanding of the needs of the patient.

The nurse wrote the passport on the patient’s behalf in narrative form. Wherever possible, she used their own vocabulary and language.

Using the patient’s own style of communication conveys their personality and character, giving them a sense of independence and ownership over this document.

Written in this way, the passport is a powerful way of establishing their individual personhood with anyone involved in their care, regardless of the setting.

Tyler Kirkham, the student nurse who led on this QI project, describes her experience of working on an improvement project in a care home environment:

‘My care home experience was hands down the best learning experience I had. Within my six weeks, I worked on quality care improvement within the home, which was supported by all staff.’

System-wide benefits

The development of the hospital passport is a complex care intervention that goes far beyond compiling a medical profile. It requires an appreciation of a patient’s clinical condition within the context of their personhood and their particular lived experience.

Using creative, lateral problem-solving skills, Tyler adapted an existing resource to enable better quality, more personalised care for individuals as they move through different clinical settings and organisations. This is what high quality, whole-system care looks like.

Following her work on this project, Tyler was given the Brittle Bone Society’s Touch a Life award.

Since writing this blog she has successfully qualified as a Registered Nurse and has attained her first nursing position in an inpatient ward at Edinburgh cancer centre.

Find out more

Read about the CHEF role supports education in care homes in Scotland

Read more about NHS hospital passports