When I was young, before it was known that tigers and many of the wonders of nature were on the verge of extinction, there was a thing people used to talk about and which would occasionally enter my dreams.

Tiger traps.

There is probably an old film out there where this features.

You take a well-trodden path in the jungle, dig a deep hole (not forgetting the ladder so you can climb-out), cover the hole with leaves and wait.

Eventually an unsuspecting tiger wanders along and falls in.

Voila.

Looking back and knowing how big the tigers are, the hole would have to be very deep; there you go.

What is the link with long-term conditions?

You could add older people to this.

You see, it dawned on me a few years ago that there is something wrong with how hospitals function; this is not to say that they are all wrong – yesterday’s blog about the profound ability of surgeons I believe demonstrated that, no, it is how we match-up doctors, and patients with either long-term conditions or in my case, older people, and, particularly those who are very old, very frail and at significant risk of deterioration (most commonly translated into either a fall or an infection.)

It’s like the tiger.

The hospital is the trap, and the doctors are sitting and waiting.

This is not to say that there aren’t folk out there pursuing the tigers (these are GPs and community staff) – it is just that there are so many other distractions that it is hard to focus (the young, the pregnant, the lonely) and, what we know about hunting is that you require singular concentration (ideally, working in teams – that’s for another day).

In the hospitals (the hole) we sit and wait.

Eventually, inevitably, the older person will fall-in; literally and figuratively. Or, the person with diabetes will go wrong, the middle-age man’s asthma will deteriorate or the young woman who doesn’t know what else to do takes an overdose.

And then the doctors go to work; ward rounds, or more common nowadays, a medical assessment unit team will be on you, doing their best to sort.

In the case of younger people, and if there aren’t too many conditions happening at once (we call this multi-morbidity), the person is fixed – their insulin adjusted, steroids prescribed or offered the opportunity to talk with a mental health nurse and they are off.

For older people where there might just be one presenting condition, when this is combined with frailty, social isolation and relative poverty, the turnaround is more difficult.

You do the tests, start the medicines and call the social worker.

And wait.

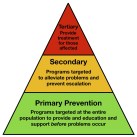

In medical circles there is a big debate about how you identify those most at risk of deterioration, or in the case of the NHS’s current mantra, the people who are ‘avoidable admissions’ – usually this is portrayed as a triangle (or pyramid), with the most vulnerable at the top (the tigers) and everyone else closer to the bottom (maybe the wood-pigeons, or some other animal that appears to be in abundance).

If you go after the pigeons, you wear yourself too thinly – we call this public or population health, where the most we can often do is a few posters on bus shelters saying things like ‘mind your waistline’ or ‘count the units’ – most of which is ineffective as the paltry sums available to public health bodies are inevitably dwarfed by the industry’s ‘Cadbury’s Caramel’ delivered by a lascivious rabbit.

And the opposite is also the case; the academics say, there is a lack of evidence, even, if you go after the folk at the top of the triangle/pyramid, of this making any significant (p<0.05) difference; you’ll be wasting your time as it is too difficult to predict who will specifically deteriorate.

Those who know me will recognise my ambivalence towards evidence and academia.

Sure, it has its place, but the arguments are usually two-directional, in as much as their being just as little evidence of effectiveness for us doing what we are already doing, it is just that tradition, or more likely habit keeps us going along the same paths (heuristics).

What has been my idea?

Well, it was to stop waiting for tigers to fall into traps and go after them in a different way.

Me, a so-called specialist, has stepped sideways and taken-on some of the behaviours of the people who see patients all the time – that is general practitioners; I have literally changed my stripes or spots (or whatever analogy works) and gone out to the practice where the (dying to say, ‘Wild Things’) patients are.

Not waiting for the trap or the referral letter, the ward round on the assessment unit; instead working in primary care, getting down to the nitty-gritty, identifying who the vulnerable folk are and sorting their medicines, their falls, their plans for the future.

In case I haven’t expressed myself well enough, the latter is another fantastic example.

It relates to Advance Care Plans.

This is something that fascinates me and, if you like, you can Google ‘almondemotion advance care plan’ to find-out more – or listen to this webinar;

These are the documents that say a person will not benefit from a return to hospital as they are too frail, vulnerable or confused; therefore, do what you can to support the man/woman, often in their care home.

These documents are okay, yet by and large, we have to wait for the person to fall into the trap and the people writing these letters are often hospital staff who really know very little about the person and in particular their social or care environment back home. Hence, they are often ineffective.

For anyone interested, I am in the process of starting-up a South Yorkshire (and beyond) Advance Care Plan group. Let me know.

Sorry; I digress.

I, having taken-on the clothing, demeanour (I hope) and behaviours of a General Practitioner can now go and blend-in with the care home residents, talk with them, their relatives, the care managers and work out how best to support them and allow them to achieve what virtually everyone wants – staying well, out of hospital and living their lives free of medical intervention.

Two and a half days a week I have moved away from waiting beside the trap, to going feral, in search of those I can help the most, where most of the patients are – not in hospital beds, but at home, in their front living rooms, sitting precariously on riser-recliners or maintained in rickety beds.

I am out, I am free, I am getting to where the action is.

Getting to make a difference to people before the worst has happened; not only do I get to meet people at home, in their own environments, free from the anxiety and stress of hospitalisation, I can sit and chat, breaking down the hierarchical boundaries that are inevitably associated with hospital life and meet people as people – as equals, perhaps doctor and patient, but certainly not hunter and hunted.

I hope this hasn’t been too obscure an introduction into my new life; I promise to write more, the next time, perhaps more succinct and without too many perambulations.

Here is to the week ahead!

Comments

Triptiatrilm 25 Feb 2024

For hottest information you have to go to see world-wide-web and on the web I found this website as a best website for most recent updates.