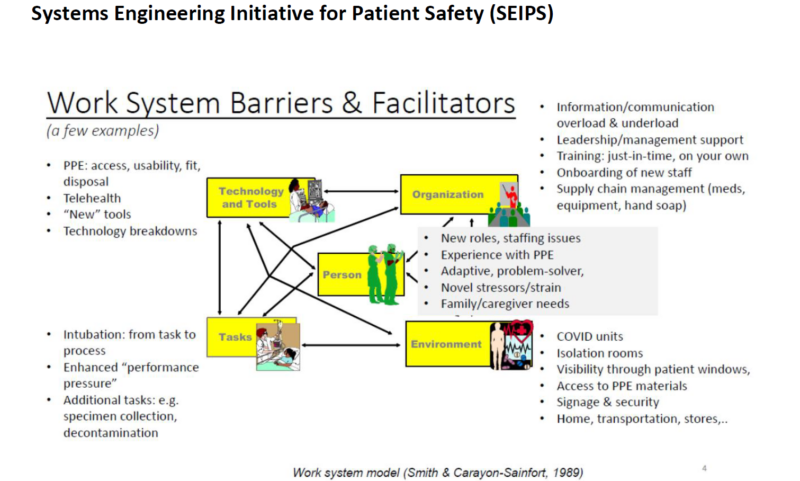

There is extensive learning to be harvested regarding how we can better support the physical, cognitive and organisational work of health and social care staff in the COVID-19 crisis. As part of COVID-19 learning in first wave, and to inform the ‘Service Reset’ programme that followed, the Northern Health and Social Care Trust (NHSCT) in Northern Ireland undertook an analysis of Human Factors and Ergonomic adaptations, through the application of the SEIPS Model; Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety, in the Intensive Care Unit in Antrim Area Hospital. The SEIPS model attests that how well a care system is designed (structure), affects the safety of care processes (process), impacting on patient, family and healthcare worker safety (outcomes). The model has five elements:

- Individuals (e.g. staff)

- Tools and Technologies (e.g. PPE, Action Cards, Checklists)

- Tasks (e.g. putting on a mask)

- Physical environment (e.g. ICU bay)

- Team and organisation (e.g. roles and responsibilities, culture, leadership)

The model was applied in-situ by a quality improvement and Human Factors professional in June 2020, by shadowing and interviewing staff and gathering data.

Why is human-centred design important?

Human Factors and Ergonomics is a discipline that examines the design of individual system components and interactions with each other, taking into account human capabilities and characteristics, with the goals of achieving optimum safety and performance. The application of human-centred design to support human performance during a large-scale health crisis can yield improvements in effectiveness of response, taking account of human cognition and behaviour. This is enhanced when the leadership approach creates the conditions for change – encouraging and empowering staff to make changes.

This is enhanced when the leadership approach creates the conditions for change – encouraging and empowering staff to make changes.

What did we find in our analysis?

- Human Factors and Ergonomics can help realign workflows to increase worker reliability under duress by designing processes that protect against systems failure stemming from human error. By deferring to experts for decision making on process (a quality associated with high performing organisations), the optimal solutions can be achieved – with process design focussed on ‘Work as Done’ as opposed to ‘Work as Imagined’. This also creates the best opportunity for mitigation of risk associated with human error, and frequent ‘workarounds’.

- Many of the most successful solutions deployed in our COVID response were very practical, capable of rapid testing and implementation, and required little resource investment, particularly those related to improving communication and team working.

- Solutions related to redesign of the facilities themselves required more planning and capital investment – though still facilitated rapidly through multi-disciplinary input, agile management response, and collaborative system leadership, working across boundaries towards a shared vision.

- Those individuals with more exposure to improvement science and rapid cycles of change found rapid adaptation less stressful. Those who gained first time exposure to the application of QI techniques in designing workflow, tasks, and an environment in response to COVID now demonstrate a clear interest in retaining such approaches to facilitate continuous improvement. They also report increased job satisfaction and meaning.

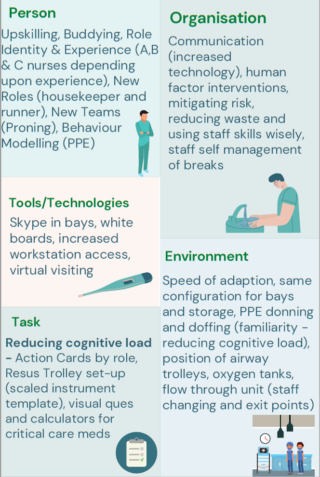

Some of the most effective interventions in the ICU during the COVID response were the simplest to implement, with a strong focus on reducing opportunity for failure of team cognition; a major contributor to almost all major incidents and inadequate emergency/disaster responses. It is possible to apply simple Human Factor interventions to improve team working and communication within the context of a challenging PPE environment. Simple adaptions which proved highly effective, included:

- Colour coded stickers to identify roles i.e. medical, nursing, proning team, pharmacy etc.

- The use of visor stickers with staff pictures, name and role identification.

- Clear identification and categorisation of nursing staff by level of experience i.e. Group A nurses had ICU experience, group B nurses had been redeployed from other areas with no ICU experience and group C staff were redeployed healthcare assistants.

- ‘Buddy system’ of nursing staff with less ICU experience with those with experience. A bay of four was staffed by two ICU experienced nurses and four redeployed nurses.

- The use of additional speakers in bays to enhance sound from colleagues communicating via Skype from outside the bay area.

And finally…

Health care, as a complex sociotechnical system with many interacting components, is well positioned to benefit from Human Factors engineering. The retrospective application of the SEIPS model has identified Human Factor and Ergonomic interventions that proved successful in the ongoing COVID response, as well as informing learning for any subsequent waves of the virus and supporting the design of the new ICU facility. It also highlights the importance of the ‘right’ conditions in which staff feel empowered to make changes, feel psychologically safe to speak up, and where decision making is deferred to experts for a particular task or situation, to take responsibility when there is a need. Other organisations may find the application of SEIPS helpful to any future outbreak response.

Have you applied the SEIPS Model in response to COVID-19, Q community? Share your experience below.