#DataSavesLives is a brilliant slogan. I’ve used it many times myself, and it was recently deployed as the title of the new draft Health and Social Care Data Strategy. But let’s be honest, streams of 1s and 0s can’t really save lives – at least not by themselves.

The new data strategy is a good one. It outlines ambitious plans to give people and professionals access to the data that they need to make better decisions, to improve data for social care, to empower researchers, to develop the right technical infrastructure and to spur innovators.

However, what really saves lives is people applying knowledge to real-world problems

However, what really saves lives is people applying knowledge to real-world problems. A patient using knowledge to choose the right service. A clinician using knowledge to recommend the most effective treatment. A manager using knowledge to organise local services. A regulator using knowledge to identify areas for improvement.

Knowledge is not data: it is the insights derived from processing data. If we really want to save lives, then we need to go beyond data and data strategies. However, #KnowledgeAppliedToRealWorldProblemsSavesLives doesn’t have quite the same ring to it, so we might be better calling our vision a Learning Health System.

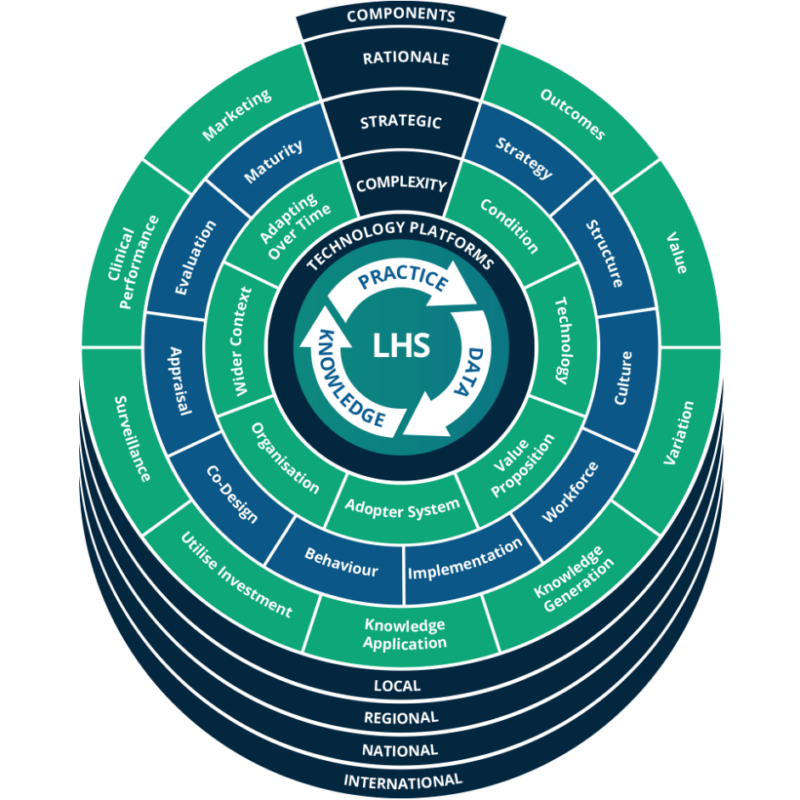

The Institute of Medicine defines a Learning Health System as one in which “science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process, [with] patients and families active participants in all elements, and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience”.

This is kind of what the data strategy is getting at, but this definition implies a lot more complexity. It won’t be met just by improving technology, interoperability, data architecture etc, or by simply giving people better access to data.

The Health Foundation funded The Learning Healthcare Project to investigate how organisations at the local, regional, national and international level could realise the potential of Learning Health Systems. We concluded that they could improve outcomes and experience for patients, improve value, reduce variation, generate new knowledge, better apply existing knowledge, make better use of our IT investments and improve clinical performance. We produced a framework to outline our thoughts on how this could be achieved.

The new data strategy will help to deliver part of the central cycle of this framework: capturing data from practice and generating knowledge from the data. It is less explicit about how the knowledge will be put back into practice. It is often assumed that giving people access to data or knowledge will change their practice. This often doesn’t happen or takes far too long.

In recent years, we have repeatedly underestimated the importance of complexity in data-driven projects. Uncontrolled complexity often results in failure, but the failures are rarely written up. In our latest report, we employed the Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread and Sustainability (NASSS) Framework to understand complexity within any given Learning Health System implementation.

To enable a successful Learning Health System, we must set a carefully considered strategic direction that goes beyond data.

Often the illness is more complex than assumed, with challenging co-morbidities or socioeconomic associations that the data fails to capture. Often the value proposition doesn’t make sense for the organisations involved. Often those organisations are under too much pressure or have limited capacity for innovation. On many occasions, we have unrealistic expectations of the patients, carers and clinicians who will actually use the system. The outside world can intervene with regulations or political realities that wreck the project. And even if you overcome all these challenges, any individual element could still change over time.

To enable a successful Learning Health System, we must set a carefully considered strategic direction that goes beyond data. We must build the organisational structures to deliver the strategy. We must create a culture of learning and a scientific approach to implementation. We must change behaviour and continually evaluate our progress. Perhaps most importantly, we must co-design all of this with our patients, colleagues and key stakeholders.

There is no “how to” guide to building a Learning Health System. It will be different in every setting. However, if you want a guide to what your organisation should be thinking about and what tools might be helpful, then check out our new report, Realising the Potential of Learning Health Systems.

The ___ report was creating in parternship with the Health Foundation