It was a pleasure to read the Quality & Safety article by Andrew Smaggus published last summer by the BMJ. At the same time I was working with colleagues from the Evolutionary Transformations Group (ET Group), on the impact on our wellbeing of the way we think about and relate to challenges in a complex world. Reflecting on my experiences as a clinician, manager and improvement lead, Smaggus’ thinking made perfect sense.

As clinicians we are confident in our expert knowledge and the mastery of our specialist skills. As a patient we are given a right answer and a clear offer of treatment or cure.

The concept of creating a new Safety-II paradigm based on concepts from complexity science is exciting and potentially liberating for both caregivers and receivers. Safety-I defines success as the absence of failure; the fewest number of things going wrong. There is a best practice or good practice ideal and clinicians are expected to act in line with this.

Snowden’s Cynefin model advocates best practice when faced with an obvious challenge, a challenge where there is a clear cause and effect relationship apparent to all involved. There are such challenges in health care and Safety-I thinking has been extremely useful in establishing safe systems to support the correct use of equipment or the best way to conduct a routine procedure in usual circumstances. In a recent visit to hospital, my temperature and blood pressure were monitored and my blood was taken. The HCA followed best practice procedures to obtain the result she needed, and I suffered no harm.

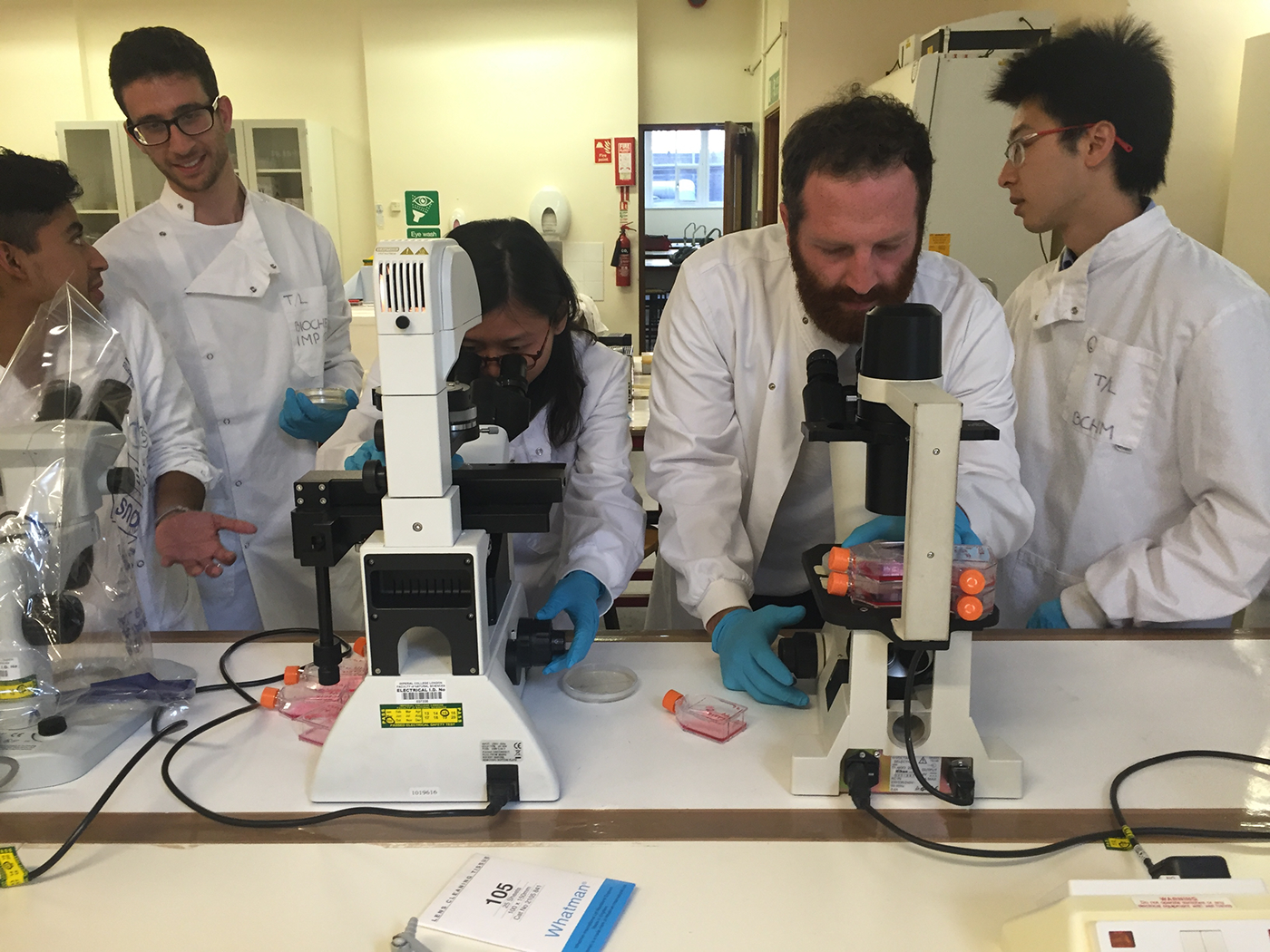

“Synthetic Biology: Externalising the Internal” by Ahreum Jung is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

“Synthetic Biology: Externalising the Internal” by Ahreum Jung is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

When faced with complicated problems the clinician applies their expertise to identify the relationship between cause and effect. In my recent experience, the doctor assessed the problem I was presenting with, analysed the information available and decided on the best response using good practice. This is a situation in health care where we often feel most at home. As clinicians we are confident in our expert knowledge and competent in the mastery of our specialist skills. As a patient we are given a right answer and a clear offer of treatment or cure.

Given the efficiency and security we experience when operating in the face of obvious and even complicated problems, it is perhaps no surprise that we often misidentify complex issues as belonging in this space of ordered challenges. As Smaggus discusses, there is a growing body of evidence that tells us what we already experience to be true, that these approaches are not successful in dynamic unpredictable or VUCA environments (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity). In these circumstances the ability to sense and respond, to provide a creative, agile and adaptable approach is most likely deliver success. Our ET Group workshops found that supporting people to occupy a resourceful state and develop confidence to access their Complex Human Adaptive Intelligence was successful in enabling them to be well and to operate successfully in a VUCA environment. In complex and unpredictable circumstances, strict adherence to best practice procedure or good practice guidelines is not advantageous.

Our focus on fails can also blind the system to the extra work being done by people to maintain good outcomes.

Smaggus identifies that the Safety-II approach which focuses on what goes well has much to teach us here. He cautions that in failing to recognise what goes right we also fail to see the things that may be exhausting and frustrating to people in their everyday work. In my experience, every health and social care worker can tell you about a standard policy or procedure that makes doing an everyday task much harder to do well. Our focus on fails can also blind the system to the extra work being done by people to maintain good outcomes. In this situation, long hours, missed breaks and working on days off and holidays become the norm. If Safety-II approaches were being applied, what would we do differently? Would caregivers and receivers be eating lunch together? Would we invest time celebrating holiday taken rather than investigating days off sick?

In our ET Group workshops, we also identified the detrimental effects of attempting to work with complex challenges when misidentifying them as ordered problems. When we do this our best or good practice solutions fail or result in temporary, unsustainable quick fixes. We merely store up more challenges to be sorted in the future or beat ourselves up with self-accusations that we are incompetent, careless or didn’t work hard enough to generate the correct solution. The way our systems and organisations respond frequently reinforce this, investigating deviation from standardised process and identifying individuals to blame and punish. The impact on our wellbeing and connection with our work is devastating.

The way our systems and organisations respond frequently reinforce this, investigating deviation from standardised process and identifying individuals to blame and punish. The impact on our wellbeing and connection with our work is devastating.

Smaggus identifies the effect of Safety-I approaches, which elevate the importance of the regulatory systems and those who design and operate them above the knowledge and experience of clinicians, and the resulting impact on engagement with work. I would suggest that there is further impact. That this approach and the paradigm it is based upon is in part responsible for sucking the humanity out of health care. The emphasis on technological solutions, standardisation and control excludes things that cannot be readily codified. We know that safe, high-quality healthcare is most likely to happen in the context of a trusting and caring relationship. Activated and engaged patients are less likely to come to harm, and valued and present staff are more able to work confidently within an unpredictable environment. These staff will be able to respond appropriately to meet the individual needs and preferences of their patients. The blanket misapplication of Safety-I and standardised approaches do not align with our aspirations to provide high quality, person-centred care.

As we continue to struggle to cope with demands on an individual, organisational and system basis Smaggus makes a vital point. It is only by adopting Safety-II thinking and appreciating how to better support the many successes of normal everyday work that we can provide the resilience and flex to enable us to continue. He identifies a very uncomfortable truth; the modern scientific paradigm is no longer enough. It has a role to play in supporting safe practice in everyday straightforward tasks but cannot address the complexity of our current situation. Continued failure to recognise this will perpetuate stress and burnout for staff and continue to create unresponsive, low quality and even unsafe experiences for patients.

I am looking forward to hearing more from Andrew Smaggus next week.

Watch the webinar: ‘The Quiet Revolution in QI: Safety-II and the Return of Practical Expertise’ – Andrew Smaggus and Suzette Woodward.