The complexity of patient safety

The NHS Patient Safety Strategy requires every Trust to have a Patient Safety Specialist an evolving role with the purpose of ensuring that “systems thinking, human factors and just culture principles are embedded in all patient safety activity”.

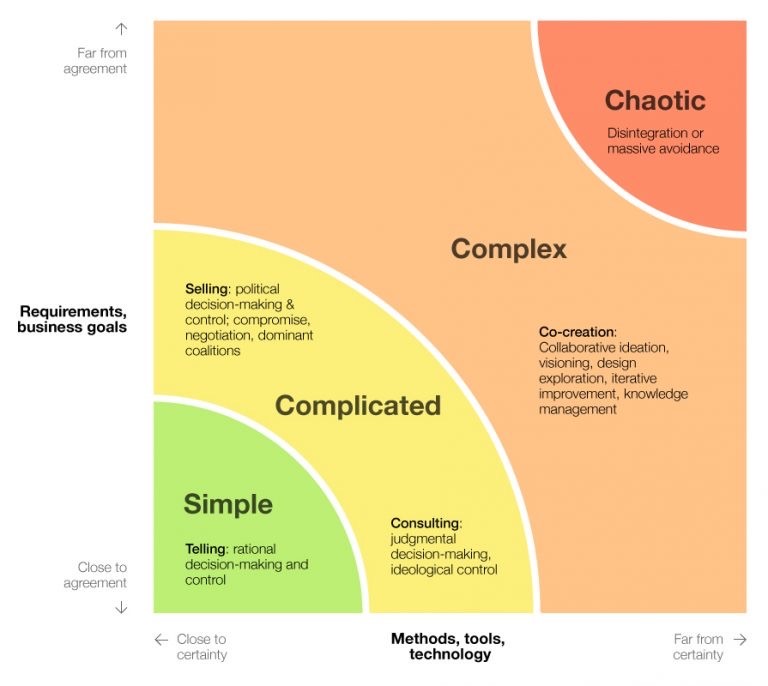

Patient safety is a big topic, and apart from a general sense of frustration that we don’t seem to be making any progress, there’s little agreement about what the problems are, let alone the solutions. This makes the subject truly complex, rather than merely complicated: as described by the Stacey Matrix (below).

There are many versions, but the one pictured is particularly effective, combining the concepts of complexity with approaches we should consider using in response. It is the acknowledgement of complexity, and the understanding that it requires a different approach which I think are the two most important messages which the new Patient Safety Specialist role can bring to an already crowded patient safety space.

This paradigm shift mirrors the development of my own journey as I have moved from being ‘Taylorist’, believing that highly structured Scientific Management had the answer (and may have uttered the words “If everyone just did as they were told everything would be alright”) to being a self-confessed “Safety Anarchist”, believing that increased bureaucracy does not equal increased safety.

I’ve since been considering how I could best communicate the models and theories underpinning my own patient safety philosophy. Some images are so recognisable that they become icons; we instantly know what they signify. I have come across a few images which represent landmarks in my patient safety journey and which have worked their way into most of my own presentations becoming my “icons” of patient safety. I was searching for a thread to tie these together when I saw this:

The manufacturer of this popular gaming controller (which uses different symbols to label its action buttons) clarified the blue symbol is in fact, a ‘cross’ rather than a letter ‘X’, contrary to how it is perceived by the majority of its users (my own son and all his friends included). It fascinated me that a modern-day icon could be the subject of such ambiguity; sometimes we really don’t know what we don’t know.

It is important to check our mental model; to make sure we are all on the same page. The common theme of my icons is how a shared mental model of complexity at all levels, micro, meso and macro, is so important. And as a Safety Leader, I believe facilitating this should underpin the development of role of the Patient Safety Specialist. Those four iconic controller buttons provided that connecting thread for my “Four icons of patient safety”.

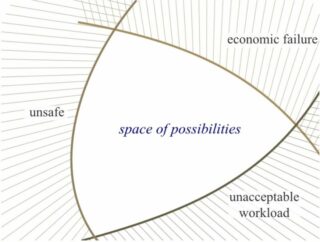

Falling under the first icon is Rasmussen’s space of possibilities, which describes three decision-making influences; “Safety”, “Workload” and “Cost”, forming a rough triangle. However, trade-offs also extend from more risk/benefit decisions, to goal conflicts where more than one desirable outcome each with its own variables exist. However uncomfortable we are talking about them, these trade-offs are inevitable. Where we sit in the space of possibilities can be very subjective and the trade-offs can become aggregates of many opinions. Not being aware of, or denying their existence fails to acknowledge complexity at a fundamental level.

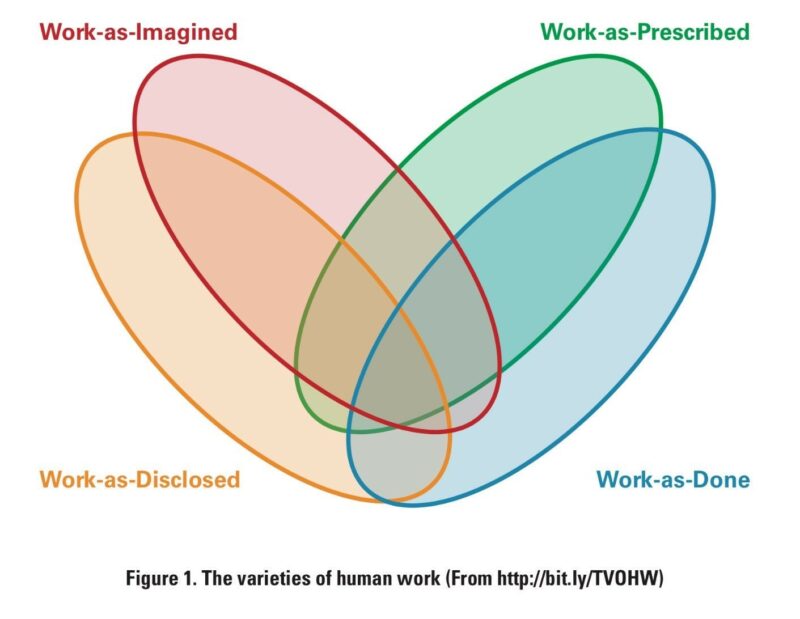

The second icon represents the four varieties of human work which I find best described by Steven Shorrock.

This elegant model describes how the very nature of “work” differs depending on the point of view of the observer, falling into the four categories shown.

The importance of the gap between these varieties of work is increasingly recognised and it’s my belief that it is both caused by and results in many of the unspoken trade-offs mentioned above. For example, many policies and metrics are created by people who do not actually do a job, meaning Work-as-Prescribed results from Work-as-Imagined. This may drive trade-offs in Work-as-Done to achieve outcomes (Work-as-Disclosed).

It may also lead to false reassurance about the work that is done, and reinforcement of existing rules when things go wrong based on the assumption they will increase safety, i.e. “if everyone just did as they were told everything would be alright”. This misses the point that, in a complex environment, it is the very ability of humans to tolerate and adapt that not only underpins safety but often actually allows anything to get done at all.

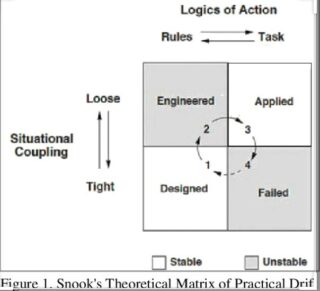

The third icon in the thread draws on Scott Snook’s “practical drift” theory, which describes “the slow uncoupling of practice from procedure”.

Starting from scratch, a well-designed system should be stable with all its components working in harmony. As time goes by, most components are eventually found to not be doing what was intended nor in quite the way they were intended to do it. This can be driven by external or internal influences, or in the case of a complex system, simply by unpredictable interactions between various components (self-organisation). The result is an applied system. However, sufficient flexibility in the system and reduced interdependence between processes can provide some stability.

One likely result of the applied system is that there is a gap between Work-as-Done and Work-as-Imagined. If, however, interdependence within the system increases, this gap can be revealed. When moving into a tightly coupled situation we have little option but to base our behaviour on the assumption that other people are following the rules even when we know we are not. That gap between Work-as-Done and Work-as-Imagined may result in an incident.

In the spirit of complexity, I do not offer a single solution as my final icon but a selection around a theme.

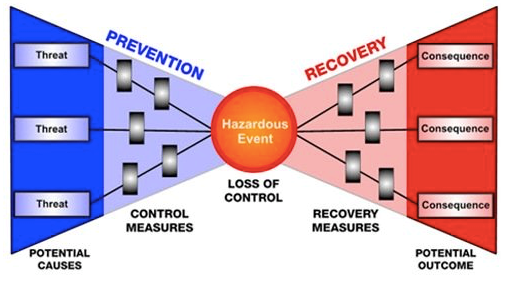

Incident investigations will still be an important part of patient safety. The Bow Tie Model (above) begins the move away from linear causation with the incident as the end result, to a more complex, multifactorial model with the possibility for both prevention of hazardous events and both the avoidance and recovery from the consequences.

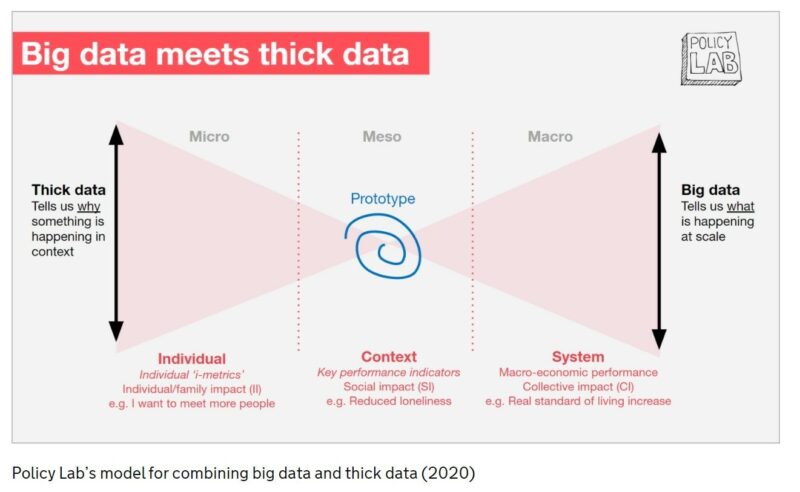

My second candidate is this slide which nicely sums up the story of complexity over the micro, meso and macro scale. It is at the point where my worlds of investigation and leadership; microscope and telescope meet (or cross) that I believe should be occupied by the Patient Safety Specialist, helping ensure that each of the components of a system is understood in sufficient detail but also to maintain sight of how these parts of the system fit together. In a reductionist approach it is easy to forget that, however well understood the individual components of a system are, they are usually fundamentally changed by their interaction with other parts of a system.

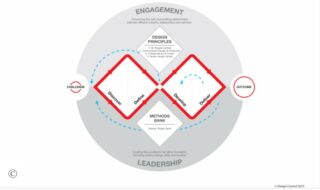

Lastly, where the causes of incidents are complex, simple solutions (aka “silver bullets”) are unlikely to be effective and in a poorly understood system may have unanticipated consequences. Again, sitting where the two diamonds of this elegant model from the Design Council cross, the safety leader should be positioned to facilitate co-creation of solutions.

In the already crowed space the Patient Safety Specialist should seek to join up the information-gathering skills of investigators, the design and implementation skills of human factors and quality improvement practitioners with the rich contextual knowledge and varying mental models of people actually doing the work together with the requirements of those using and providing the services.

So what is the role of the Patient Safety Specialist? That’s a complex question…

Do you have a philosophy on patient safety, Q community? Leave your thoughts below.

Comments

Thomas John Rose 1 Mar 2024

I have a philosophy on Patient Safety - It's Process Management - but first processes have to be designed and documented. The documentation HAS to represent WADone and not WAI, WAP or WADisclosed. See BS ISO 7101:2023