Learning fast and systematically might not seem like an obvious priority for an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) set up rapidly in a conference centre to deal with seriously ill patients during a pandemic. Yet the uncertainty of the situation, the constraints faced, and the huge demands on the team at London’s Nightingale Hospital made it essential.

Only by learning rapidly and systematically would we be able to keep our patients and staff safe.

Hospital inception to receiving the first patient at London’s Excel Conference Centre happened in under three weeks. Only by learning rapidly and systematically would we be able to keep our patients and staff safe. We were dealing with substantial uncertainty on several dimensions: a new disease, a novel care setting and a workforce drawn from many institutions, with many staff unfamiliar with an ICU environment working long shifts in full PPE. To address these challenges we built a closed-loop learning system that gave staff a voice and created ways to quickly fix problems, then test and implement learning back at the bedside.

A key insight was that, whatever people’s background, profession or experience, staff who are brought into a system that fosters learning become valuable improvement agents – almost by default. This isn’t to take away from the important work of improvement teams. Rather, it’s to put learning where it should be – a mainstream activity for everyone involved in health and care.

It’s a privilege to be part of helping to set up @NightingaleLDN

Quality and learning are core to its work. Milestone today for the opening in just 10 days

Incredible teams working round the clock to officially open today! Thanks to all who have led, contributed and supported pic.twitter.com/9h1vumNfZ0

— DrDominiqueAllwood (@DrDominiqueAllw) April 3, 2020

What do we mean by a ‘learning system’?

Creating a learning system in a health care environment isn’t new. In the US, for example, many organisations think of themselves as learning systems – but it is novel to the NHS. Organisational learning systems:

- are interested in design and implementation

- integrate qualitative and quantitative data from multiple sources

- learn in a systematic way from internal experience as well as external published research

- test and modify new approaches rapidly in order to put insight into action, as part of standard, daily work. There is no ‘doing’ without also ‘learning’.

We set out to create a system at the Nightingale that integrated learning with clinical and managerial governance. Central to our approach was building a connected system which focused on resolving key uncertainties toward safe, effective and compassionate care for our patients and the welfare of our staff.

This was March and April 2020, the early days of the pandemic. England locked down two days before we joined the Nightingale team. At that time, the world’s knowledge of the virus’ clinical effects, infection control for COVID, and working in full PPE was rudimentary, and very fast evolving. For example, a week into our work, it started to emerge that COVID wasn’t just ARDS/respiratory failure, but had far more systemic, multi-organ effects. We had to rapidly incorporate this learning into our clinical model and routines.

What did we do at the Nightingale that was different?

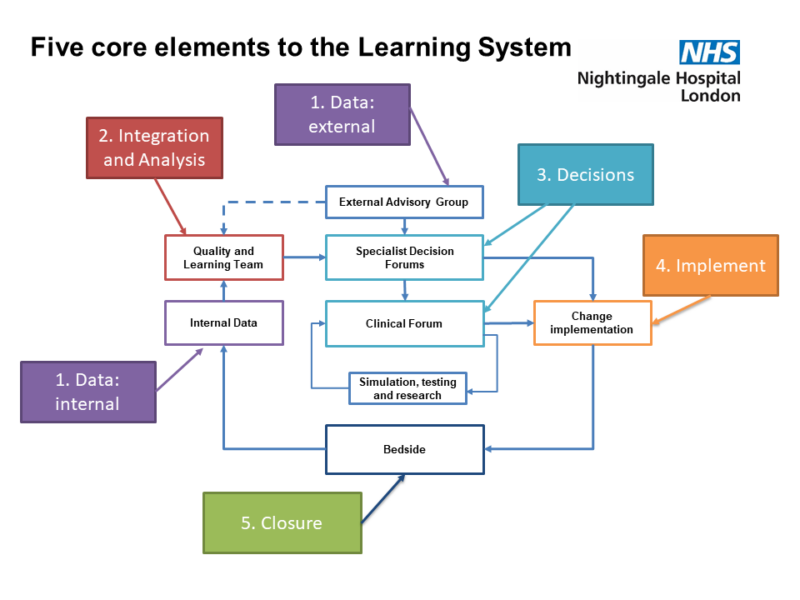

The Nightingale’s operating system embedded five key learning system elements in our organisational structure, daily routines, and the cultural ethos, so that learning became integrated into everyone’s work. This focused discovery and testing, sped-up decision-making, flattened hierarchies and reduced bureaucracy.

The ‘data-in’ element focused on what data was needed to drive key decisions. This spanned qualitative and quantitative data, patient, family and staff data, and risk and governance data from our own operations together with evidence and experience data from the rest of NHS and globally. We introduced the role of Bedside Learning Coordinator (BLC); they acted as the eyes and ears of everyone on shift to gather insights, to take that information out of the contaminated zone and to inform decisions on what needed to happen. They would then help to bring that change and learning back to the bedside and help to communicate changes widely. These supernumerary staff were usually clinical staff (nurses, AHPs, medics) who were also working standard clinical shifts at the Nightingale, but some did not have clinical training (for example, a health care manager or logistician). Most fed back that doing shifts as BLCs helped them see their usual clinical role differently and to further promote learning.

We categorised and triaged the types of problems observed at the bedside into three buckets: fix, improve and change.

Data were collated and evaluated by the Quality and Learning team, which included the Clinical Governance group. This meant that at Nightingale different types of data which typically are integrated only remotely (sometimes at the Board or its sub-committees) were brought together very early and usually daily. All data went into a single analytic frame, which fed into the various decision-making forums. Every day we brought together a forum of clinicians, managers, healthcare professionals and non-healthcare professionals to talk about the problems we encountered and the learning from them. These were open and inclusive of everyone, with a focus on learning and change.

We categorised and triaged the types of problems observed at the bedside into three buckets: fix, improve and change. ‘Fixes’ rarely needed further evaluation and testing and could be implemented straight away – such as putting rest areas within the ward area so staff could take a short break without the need for full doffing and re-donning. Improvements and changes were subject to further testing and peer review, and took the form of more typical improvement mini-projects (such as changes to the donning regime) or redesign of basic protocols (such as extubation).

What were the enabling factors?

Nightingale was not a perfectly smooth operation, and we faced multiple challenges and emerging problems. Nevertheless, Nightingale functioned, in very short order, as an ICU, with patient outcomes comparable to base hospitals, and generally very strong staff experience metrics. We highlight four enabling factors which underpinned this:

- The Nightingale had a clarity of shared purpose, from day one, that we were all there to protect London and to save lives and to do whatever we could to ease burdens on staff on the clinical floor.

- We made listening to staff, capturing learning and implementing ideas central to what we did.

- We built a system to capture data of all types relevant to our most pressing challenges and provided a basis for action to resolve our key uncertainties.

- Finally, we were able to create a sense of belonging as ‘one team’ across all roles and professional backgrounds which was real and went way beyond a slogan and the usual scope of the multi-professional clinical team: cleaners, porters, supplies staff, the Chaplaincy and many others. All had a clear role to play and all were essential parts of the team caring for our patients and staff.

What we saw in terms of better patient care, a ‘one team’ approach and a culture of learning and improvement is not just relevant to the very particular crisis situation in which we were operating. Despite differing clinical models, the learning system designed for ‘Nightingale 1’ has been successfully implemented a second time in ‘Nightingale 2’. The role of the Bedside Learning Coordinator has been adopted in several hospital Trusts and is the subject of one of this year’s funded Q Exchange projects.

We hope the legacy of the Nightingale learning system approach can spearhead rapid improvements in a range of health and care settings, in the NHS and elsewhere, and in future efforts to tackle COVID, and beyond.

Further information and links

Find out more about the Q Exchange project: Everyone can be at the frontline of Quality Improvement

Learning Systems: Managing Uncertainty in the New Normal of Covid-19: NEJM Catalyst

Alternative Care Sites for the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Early U.S. and U.K. Experience: NEJM Catalyst –

10 Leadership Lessons from Covid Field Hospitals: HBR

Systematically capturing and acting on insights from front-line staff: the ‘Bedside Learning Coordinator’: BMJ Quality & Safety