In our webinar, we looked at pragmatic ways to describe quality to those who contribute to quality in an NHS trust.

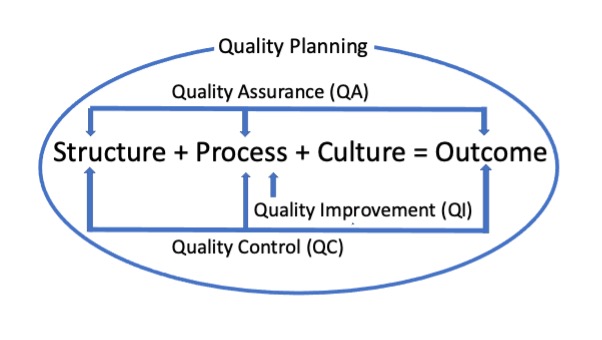

The webinar focused on four systemic and linked activities when managing quality:

1. improvement

2. control

3. assurance, and

4. planning

We looked at how each of these plays a part in QMS and the organisational learning that comes along with that. Words and phrases like definition, system, framework, co-production, language, approach, journey, culture, intended and realised strategy are all relevant when it comes to QMS.

The discussions highlighted the complexity within the NHS where the workforce in clinical and operational settings, including patients, may hear ‘QMS’ and be none the wiser in terms of its role in quality and what it actually means.

Back to basics: outcomes, structures, processes and culture

When I used to play football, we used the term ‘back to basics’ when things didn’t go as expected for our team (we focused on breaking down complex plays and getting the little things right first).

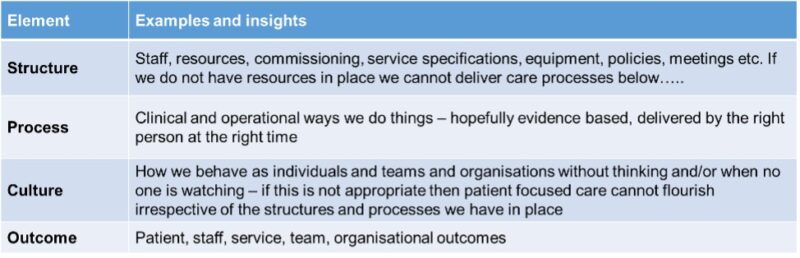

When helping staff, teams and users of our services to improve quality as well as carry out quality improvement, I use a similarly simple approach, which has four components:

1. outcomes

2. structures

3. processes and

4. culture (organisational, team and individual behaviours and actions)

Put simply, outcomes are what you get when you combine structures, processes and culture. Teaching from Donabedian and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has adapted this into a formula:

structures + processes + culture = outcome

In combination with data, narratives, feedback and local contexts, this basic formula allows me to put together a coherent, richly informed picture about why outcomes may be as they are.

Going back to basics helps to unbundle some of the complexity and variables all interplaying in NHS settings from a quality of service delivery point of view. This is also a useful approach to use when planning for quality using evidence-based structures and processes to meet the needs of those that services are designed for.

Quality Assurance (QA): evidence and standards

When evidence-based guidance and standards are used as a criterion for measuring care, we can call this quality assurance. We can apply the S+P+C=O formula to understand what care delivered is actually like by data from structural measures, process measures, and outcome measures (see QA in the diagram).

National clinical audits are a good example of this particularly when audit is combined with feedback to try and help with potential actions to improve quality.

Although helpful to understand what care delivered is actually like against standards and guidance, there are other elements of quality where there is no guidance and/or standards but this impacts on performance of teams, services and individuals within the NHS.

Quality Control (QC): how services are performing

Understanding how services are performing to meet needs, demands and fluctuations, including seasonal variations, is fundamental for clinical and operational teams to be able to try and deliver quality in real time, based on real time feedback (see QC in the diagram).

Within the NHS this is sometimes referred to as quality control. In this instance the S+P+C=O formula can help with determining from the ground up what information and data teams may need to help attain or sustain the intended outcomes based on structural and process data.

Quality Improvement (QI): testing and measuring change

The S+P+C=O formula is particularly useful with complex problems which require appropriate stakeholder engagement and time to try to understand the why.

I think 80% of improvement is understanding the problem and 20% is actually trying to do it.

This helps ensure that focus is on process changes that can be tested through prediction and measurement (see QI in the diagram). Testing and measuring whether those predictions occur in actual process change is commonly referred to as quality improvement through various approaches including model of improvement, lean, six sigma to name a few examples.

The formula can help in trying to understand if the necessary structures for process change are in place prior to any changes being tested. This is where for me, we get deviation from the traditional Juran Trilogy definitions of quality improvement and quality control. The principles are similar although operational implementation within the NHS, when compared to quality professionals in production sectors differ.

The exception being perhaps specific NHS diagnostic or laboratory departments where the international organisation for standardisation (ISO) requirements of QMS actually are being met.

Quality planning is the third element of the trilogy where definition and application within the NHS differs. But I think that is ok as long as this gets the discussion going and towards the same outcome – we have to start somewhere!

Gathering evidence and insights – help with quality planning

To establish a starting point for bringing QMS into an organisation (see quality planning in the diagram), it is vital to gather evidence and insight on structures, processes, culture and outcomes – the whole lot.

A great way to gather evidence about quality in an organisation is to ask teams some simple questions about quality.

Below is a list of quality-focused questions to get started:

- How do I (we) know that I am (we are) are doing a good job?

- Do we know how good we (our service/team/ward/unit) are?

- Do we know where we stand relative to the best?

- Over time, where are the gaps in our practice that indicate a need for change (ie improvement / innovation / transformation / research / evaluation)?

- In our efforts to improve, what’s working?

- Do we know/understand where variation exists in our team/organisation?

- Why are we measuring all this and what difference is this actually making to the quality of services and our users of service?

Aside from quantitative data and metrics, teams also need qualitative data, usually in the form of narratives and patient stories in order to establish a picture of quality of care informed by all parts of the system. Assuming you have this in place, this is for me where the most important part of the QMS could thrive – the sharing and learning of these stories and data to improve quality!

Recent work by our Scottish colleagues refer to this as a learning system in their QMS framework for the organisation, staff, teams, individuals and users of service including the local populations.

There are however foundations that need to be in place for QMS to flourish such as:

- a vision and purpose to prioritise quality

- investment in staff (example of structures) and quality being everyone’s responsibility (example of culture) through appropriate leadership behaviours

- focus on improvement capability for the workforce (example of processes)

- patient leadership to be embedded to drive innovation and change in patient and workforce needs being met (example of outcomes)

These are some important elements to think about.

Implementation of QMS

Any QMS approach needs to be communicated as an approach which, through appropriate levers and leadership, anyone within the organisation can understand. Helpful things to get it implemented across the organisation could be a suitable action plan, deliverables and measurement.

The organisational structure, systems and processes are important for taking strategic decisions about whether to introduce a framework for quality management or the recognised ISO 9001 standard.

A key point to consider is whether to have quality management professionals help with design and implementation.

A QMS approach should be supported at a strategic decision-making level, and should aim to develop support amongst staff and key stakeholders, including all departments with a quality remit such as patient safety, clinical effectiveness and patient experience.

First steps

A useful start may be to conduct an organisational audit to ascertain which requirements of QMS may already be in place in your organisation.

Introducing QMS is a must for an organisation’s learning journey. However whether the right conditions are there for QMS to thrive should be a first question. This then begins an evidence-based understanding of the current state of quality from all parts of the organisation – going back to basics.

Comments

Thomas John Rose 21 Mar 2023

I like the idea of 'Back to Basics'. In fact it was the subject of a past (2018) Q Exchange idea if mine that got some interesting comments but no funding. See https://q.health.org.uk/idea/2018/back-to-basics-lets-get-our-terminology-right-when-talking-about-qi/#commentform S+P+C=O is a great formula but QI is no substitute for an effective feedback loop for the system.

A key element of a QMS is how non-conformance is addressed. I know that the NHS get hung up on terminology nevertheless this requirement is key to a valid QMS. Non-conformance first has to be identified and a non-conformance report (NCR) generated. Corrective action is then taken followed by preventative action. Evidence of this activity is an important aspect of Audit and QA. It's important that the NHS find a way to incorporate such a process into their QMS. This process applies to all work and is in no way only relevant to the 'production sectors'.

Mirek Skrypak 21 Mar 2023

Thanks Tom and for your insightful comments as always. QI is definitely not a substitute for an effective feedback loop. Ideally QA or QC activities should propagate and drive QI if appropriate to eliminate/reduce errors, variation and waste in the system. Breaking this down through the simple formula and by looking at outcomes might help NHS organisations ensure that their departments which focus on quality ie patient safety, effectiveness, performance, audit, QI teams etc work together at a systems level as opposed to fragments of quality that they feel they are responsible for.